© Creative Commons src trimmed

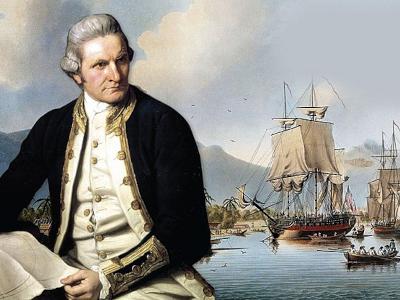

Captain James Cook started life as a son of a farm-worker on a Yorkshire country estate, but ended up a household name through his world voyages of exploration and his untimely death in Hawaii. He discovered many ‘new worlds’. What does his work tell us about the world ‘in a state of nature’ and God’s work in it.

Cook was apprenticed as a seaman to a merchant ship-owner and became adept at practical navigation. He later volunteered for the Royal Navy, offering more opportunity and with his navigational skills became ‘master’ (Petty Officer) of a brig during the Seven Years War with France. His astute charting of the St Lawrence river greatly assisted the defeat of the French by General Wolfe in Quebec. You can get closer to this history at Wolfe’s house near Sevenoaks, Kent.

With later small-ship command experience and excellent surveying skills he was commissioned as Lieutenant and put in charge of the 1768 expedition to the Pacific which unusually had a dedicated scientific team led by Joseph Banks.

James Cook recorded the actions of the ships in a journal - similar to a ship's log - but more aimed at the Admiralty. An edited verson of this is in the thick paperback: James Cook: The Journals (Penguin Classics).

His mission – explore the South Seas, spread British diplomacy

His ship Endeavour, was small – just over 100 feet but as a merchant ship she was strong, seaworthy and could hold sufficient stores and trading goods for the 3-year voyage. After working through the islands at the tip of South America, Cook reached Otaheite (Tahiti) to set up a base to observe the Transit of Venus. The results helped determine the distance of the earth from the sun. You can still visit Point Venus today.

Tahiti had been visited a couple of years previously but the chief the British had befriended had been superseded by a rival on the island. This reflected a pattern of constant conflict between the islands in an archipelago or even different clans on larger islands. Later on Cook would be invited to side with one group, ‘your friends’, against another but Cook always refused.

Some islands had population enclaves from other islands a bit like the Greek/Phoenician colonisation of the Mediterranean where a group of young well-armed men turn up in a boat and ‘invite’ the local chief to give them resources. The local ruler may not have the ruthlessness or concentration of forces to eject them and unless they are wily or lucky the interlopers will muscle in and an enforced coexistence begin. This will usually involve the loss of young local females.

To boldly go… Terra Australis

Cook sailed west reaching a land thought to be that sighted by Dutchman Abel Tasman, who had only touched on the west coast. Cook sailed round what turned out to be two New Zealand islands. Interactions with natives were uneasy and it was clear they were warlike with each other and practised cannibalism. Sailing west from there Cook reached a natural harbour he named Botany Bay. Only the northern tip of ‘Australia’ had been seen by Europeans as the main merchant routes were to India and the Spice Islands (Java etc) hundreds of miles to the north. These were hazardous enough and there was no reason to travel further. So it needed this special expedition to boldly go… In ‘Australia’ it was hard to meet any native people as they usually disappeared whenever a small boat landing was attempted. They recorded the first encounter with Kangaroos!

His second voyage was on a new but similar ship, Resolution, with consort Adventure. He was to travel as far south as possible to see if the great southern continent ‘Terra Australis’ existed. Cook encountered ‘Ice Islands’ and the southern ice sheet and deduced that there had to be land further south for the fresh-water ice to form on, but it would be of little practical use and dangerous to explore. His third voyage was to chart the hoped-for north-west passage above Canada. He discovered Hawaii en-route.

First contact procedure

Cook's approach was always seeking peaceful trading encounters with native populations. He was constantly seeking fresh water, fresh fruit, meat and fish (to avoid scurvy). He kept close control over the trading ‘exchange-rate’, iron nails being the most sought after commodity, to ensure they could still trade for sufficient fresh food.

When landing he would carry a green palm branch, then try to determine who the real chief was (of this village or island or group), exchange gifts and get permission for water and wood.

There was no sense that the Polynesians were seen as intellectually inferior or having a lesser moral capacity, but it must have been hard to respect them as they did not seem morally serious. They would routinely deceive and try to out-wit the crew if it suited them. Theft was endemic and caused the most friction, especially when the items were key to the ship’s functioning. Some modern commentators excuse this, claiming Cook didnt understand local customs, but it was clear everyone knew exactly what they were doing.

Cook allowed individuals to join the crew as interpreters, so he had a good idea what the rituals and customs meant.

Māori response

It’s intriguing to speculate about what the local people thought of the arrival of these ships. They were technological marvels compared to the relatively simple native canoes and the islanders explored them avidly, but did not seem overawed by the Europeans. A key part of this would have been the obvious good intentions of Cook and his toleration (up to point) of the kleptocratic activities. Cook’s crews relied heavily on the goods that the islands could provide, they were clearly out-numbered numerically and the Chiefs would have understood this dynamic. Cook’s ships used their guns’ noise to frighten if the ships were getting overwhelmed, and demonstrated what muskets could do by shooting game. These tactics generally kept the relationships level enough: ‘peace through strength’.

The smaller islands are just dots in a vast ocean and, apart from Melanesia, have similar cultures and language, so clans would have spread from one island group to another. The navigation skill of the Polynesians is often noted but they would not undertake long exploratory voyages unless they were forced to – not least as they would not know where they were going and without compass or sextant, not sure if they could ever get back.

Social structure

Social complexity varied with the size and remoteness of islands. In larger populations there were strict hierarchies of chiefs and peoples - who could or could not eat with another or stand in their presence. Polynesian woman were likewise stratified but always under the men of their rank. There was little value placed on the human life of the ‘lower orders’ who would be killed at the chief’s discretion. Royal Navy life was disciplined but Cook prided himself on not losing a single sailor to scurvy (or other illness if he could prevent it).

Diet, clothing and tools varied depending on the local resources. The only domestic meat was the ubiquitous ‘hog’ which must have been transported with the early settlers. Yams and other plants like Cava were cultivated in small plots.

Cook deplored the associations of his men with island women but found it impossible to stop especially as the women were willing and were offered by their men despite the spread of disease. This is justified by modern commentators as gaining status, 'gift exchange' or having 'open attitudes' towards sex. They were not of course 'open' but baked into local culture.

A more detailed account of customs and conflicts was given by a young Englishman William Mariner who survived a native attack on his small whaling privateer in Tonga in 1806 and was adopted by the local chief. He learnt the language and culture, even sharing in the tribal battles. After 4 years he was able to escape on an American ship.

In warfare cannibalism was carried out by some, said to be absorbing the power of foes.

Beliefs

They had a sense of the worship of different gods, and priests to carry out rituals. There was the universal fear of displeasing the deities and thus actions needed to placate them. There were ‘taboos’ of activities, or eating certain foods. Sometimes human sacrifice was practised. The religion was also supporting the social structure, especially the prestige and legitimacy of the chiefs. Some people seemed to experience ‘possession’ by the spirits of dead predecessors.

Cook took a close interest in the ceremonies, especially when it affected diplomatic prestige. He observed that people would be present but unengaged in what was going on. Cook did not seem to have an ‘evangelical’ faith but he would have carried out Divine Service at least every Sunday on the ship and conducted burial services at sea. He would have expected deference for religion and moral-seriousness from his men.

There is the concept of 'mana' (prestige) which could be enhanced with gift exchanges of all kinds, associations with significant people (like Cook), rituals, victory over enemies.

Cook's death

Cook discovered the Hawaiian islands on his way to explore the north-west passage on the third voyage, which could only be done in summer. He stopped at one and decided to return to explore the others during the next northern winter. He spent weeks cruising off the islands as they saw few landing places and abundant surf. In the spring 1779 they finally found a bay on the big island. On landing Cook was treated with great reverence with many people crowding to see rituals in a shrine near the beach. After collecting stores he left but then a problem with the foremast forced a return. The local people were now less welcoming. One of the ship's boats was stolen and in trying to force its return Cook was killed.

Why the change in attitude? It's thought that Cook was the embodiment of the fertility god that was celebrated at that time of year as he'd been seen sailing offshore and then arriving. In their myth the god was supposed to leave after a short visit and make war on the next island. There are various other related circumstances but a lot of the chief's and priest's prestige had been committed to the reception of Cook, so to see him breaking the narrative had to be handled somehow, maybe branding him as an (unwitting) imposter. There is now a memorial to Cook on the coast near a town named after him. It's a popular spot.

Conclusions

What conclusions can we draw from a Christian perspective, what would later Missionaries think?

* All cultures are not equal. God set the Hebrew nation in place with specific spiritual insights and rules of life, to be an example and model. Christians would have the same view but with the fulfilled promise of redemption and the Holy Spirit’s presence.

* Modern reflections on culture however take equality as a starting point – only possible if you have no objective standard for human activity and somehow believe the ‘state of nature’ is ideal, without actually trying it! How our education system needs re-grounding on objective truth.

* The local culture seemed to be one of ‘Lord of the Flies’ type survival to a greater or lesser extent. Take what you can get, defend yourself and family interests, much like the ‘Wild West’. The more conflict the greater social and economic poverty.

* Missionaries were bringing a new message about the spiritual world but also of social mores – on the sanctity of life, the stability and exclusivity of marriage, defensive warfare, nurture of a wider range of vegetables and livestock. But for this to work local people had to see the value of what was being taught in the lifestyles of the Christians.

* Although thinking the Europeans were a bit of a soft-touch, Polynesians recognised their superior technology and social organisation. They also needed allies in trading and statecraft. Having a European in a chief's court was prestigious. Christian teaching and example had a growing effect on the islanders.

* We need to recapture the social-transforming aspects of our faith that are central in the Bible and have the courage to speak of them. How hard it is to get preachers to raise the moral issues of our day, with every one of the Ten Laws of Life being actively opposed! Modern Europeans adopt false beliefs about gender, climate, economy, sexual activity, their origins and destinations, but to change they need to see that ‘God has an opinion about everything’ (John Piper) and that His way is a far better even if they don't see it all. We will still seem a ‘soft-touch’ but underneath is His healing sovereign power.